Reference list

Books

Steppenwolf, written by Hermann Hesse, published by G. Fischer Verlag in 1927 (Germany)

Francis Ford Coppola by Robert K. Johnson, published in 1977 by Twayne Publishers

The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film by Michael Ondaatje, published in 2002 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Web Sources

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wlwdpNw1FW8&feature=player_embedded – [accessed on 29th September 2010]

http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/cop0pro-1 [Accessed October 10th 2010]

http://www.interviewinghollywood.com/videos/video-416.php [Accessed October 10th 2010]

http://www.steveakash.com/robertshields/robert.html – [accessed on 12/10/2010]

http://www.robertshields.com/robert.html – [accessed on 12/10/2010]

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/watergate/part1.html – [accessed on 07/11/2010]

http://www.filmsite.org/blow.html – [accessed on 15/11/2010]

http://www.spybusters.com/History_1965_Hal_Lipset.html – [accessed on the 17/11/2010]

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yg8MqjoFvy4 – accessed on 27/11/2010

Film

The Conversation, directed by Francis Ford Coppola and released in 1974 by American Zoetrope & Paramount

Critcal Review

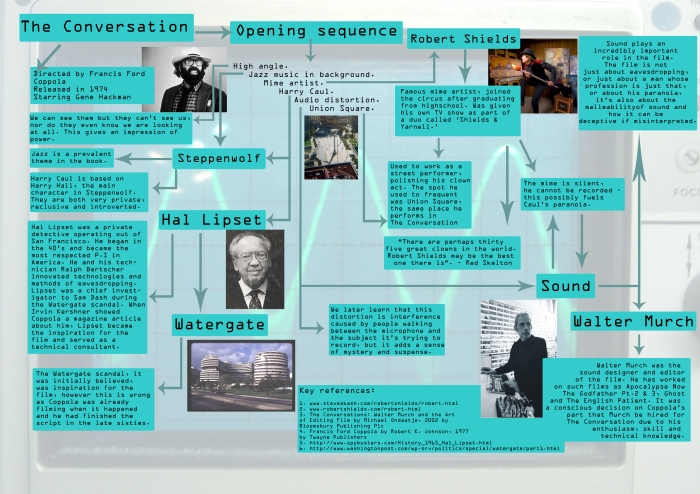

For the past two months I have been researching and studying the opening sequence for Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation which was released by American Zoetrope and Paramount in 1974 and stars Gene Hackman.

The scene I have been analysing is a single shot, just over three minutes in length, and overlooks Union Square. It starts off quite far away and zooms in slowly, focusing on a mime performing in the square. The mime follows several people, mimicking their actions and it’s when he does this to Harry Caul, Gene Hackman’s character, that focus shifts from the mime to him as he walks off.

By 1974 Coppola was already a respected filmmaker, having made The Godfather previous to The Conversation. His father, Carmine Coppola, was a musician and composer and the family put great emphasis on “talent”, which worried Coppola until his twenties when he discovered that his own talent lay in directing. He worked with Roger Corman on several projects before creating American Zoetrope in 1969 with George Lucas. [1]

It seems Coppola was influenced by Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow-Up. In Blow-Up, the main character – who is a photographer – while photographing a couple in a park, unwittingly captures a murder on film. Another influence seems to have been Hal Lipset, a private detective who innovated techniques and technologies in the field of eavesdropping. [1, 2, 3]

While watching the clip, several questions jump out at the viewer: what’s the purpose of the mime? Why such a high angle? What is the distortion? Why does Caul evade the mime? Most of these questions are hard to answer unless the viewer watches the whole film, and many of the themes in the opening scene are prevalent throughout, such as the jazz music – Caul’s only source of pleasure as a saxophone player; the angle – it reoccurs in the final scene; and the general theme of sound.

Sound is the most important theme of this film. Its use was of critical importance to give the film any substance or meaning, and the fact that Walter Murch crafted the audio with almost surgical delicacy is obvious to all who watch it. Even the presence of the mime is a statement on sound and eavesdropping; he is almost the antithesis of them, and as far as either one are concerned he might as well not exist at all. The jazz music gives a sense of carefree enjoyment – possibly most people’s view of the world, especially a park in which people are supposed to enjoy themselves without fear of being watched – and it’s when the interference cuts off the music does the sense of something more sinister and unseen surface, that even in this place someone is still listening. It’s interesting that all this can be portrayed without a single spoken word; thus is the importance of sound.

But on the other hand would the sound have the same impact if the film had different imagery? What would the opening scene be like without the mime? Or if the camera was on ground level? It would have been very difficult to portray Caul in such little time without the mime there to challenge him, and without the high-angle shot there would be ne sense of power over Caul or of a slight mystery as to what it is exactly that is watching them. Of course we learn soon after this scene that the viewer is looking through a microphone with a telescopic lens attachment, but without that knowledge it is easy to assume that it is a rifle scope. The mime, throughout the sequence, mimics the actions of others, but with each portrayal he manages to insert some form of personality to his behaviour. With Caul, however, he is so anonymous that not even the mime can work out a personality for him. [4]

The park, as previously stated, is supposed to be a place, while being a public area, is also private because nobody is listening to anyone other than the people they are with, or at least that’s how it’s meant to be. If the setting were anywhere else it is doubtful that it would have the same effect. And while sound is one of the main themes that drive the story, it is not more important than any other theme used – paranoia, for example. Without this, Caul would have nothing to drive him throughout the film

So while sound is one of the most important themes of the film, it is not the most important aspect of it. The film’s use of imagery is also crucial in understanding what is happening and to find deeper meaning within the work itself. Cleary not one aspect of this film is more important than any other, but together they create a theme and a film as relevant today as it was in 1974.

[1]: Francis Ford Coppola by Robert K. Johnson, published in 1977 by Twayne Publishers – pages 4 & 5

[2]: The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film by Michael Ondaatje, published in 2002 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc – page 152

[3]: http://www.spybusters.com/History_1965_Hal_Lipset.html – [accessed on the 17th/11/2010]

[4]: The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film by Michael Ondaatje, published in 2002 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc – page 263

Writing Plan

Introduction

I will begin by introducing the film, Coppola and his collaborators (Murch, Lipset) and giving a brief description of its themes, the decade in which it was made and its influences.

Argument 1

- The use of sound was the most important aspect of this film, both as a theme within the narrative and from a technological point of view during post-production.

Argument 2

- The use of imagery is just as important as the use of sound.

Summary and Conclusion

At this point I will summarise all points brought up by each argument and come up with my own conclusion with the evidence I have.

Research Findings

In order to express my research findings, it is necessary to return to my initial questions:

- What is the purpose behind the chosen angle?

- What is the meaning of the mime? Is there a meaning at all?

- Why does Gene Hackman’s character try to avoid the mime? Is it deeper than mere annoyance?

- Why a San Francisco park?

- What is the interference and does it have a meaning?

At he beginning of this blog I stated that:

I chose this clip against all the others because there seemed, at first glance, to be less meaning in the events in this video and I felt it would pose more of a challenge to me. There is in fact just as much meaning in this as in the others, and it’s this subtlety that convinced me to pick The Conversation as my subject.

I knew from the beginning that there were layers of meaning within the clip that had to be researched in order to find that meaning, and I was right.

To gain an understanding of my subject these questions would prove to be of critical importance to me not only to establish context socially and historically, but also to learn about the influences that helped make this film what it is and to find out more about Francis Ford Coppola.

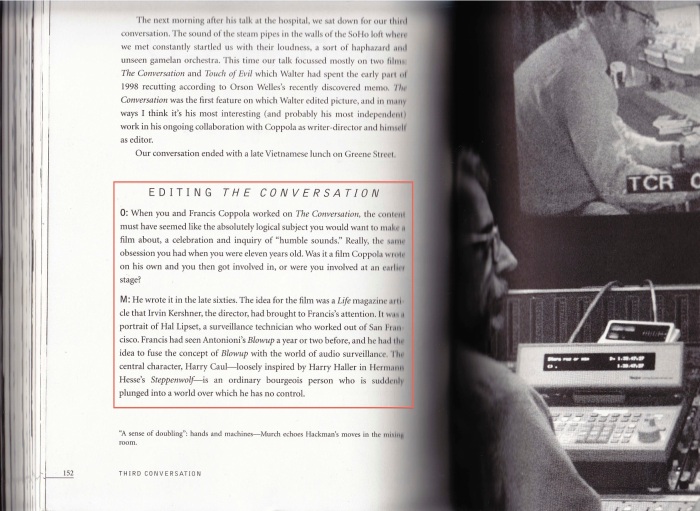

To my mind my focus has been on the aspect of sound throughout this blog, how the sound plays an important part within the film and even the clip on its own. My research into Walter Murch revealed just how difficult the sound recording was for the film and the methods they used to get around it.[1]

It was this interview with Murch that enlightened me to five things: Touch of Evil by Orson Welles, Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse, Blow-Up by Michelangelo Anonioni, Watergate and Hal Lipset [2] – who were mentioned separately in the interview, but are actually related themselves. I discovered that the initial break-in at Watergate happened while the film was being made and that the script had actually been written in the late sixties [3] [4]. The inspiration for the film came largely from an article in Life magazine about Hal Lipset, a private detective who began his career in the 40’s. Lipset would serve as a technical consultant and possibly a model for Harry Caul. Lipset also served as a chief investigator to Sam Dash on the Senate Watergate Committee. Touch of Evil may very well have inspired the opening shot as they are both around three minutes long, are both single-shots and they both follow two different subjects at various points. Steppenwolf‘s main character Harry Hall served as the main inspiration for Caul in that they are both very private an reclusive and Blow-Up was a huge influence on the whole script; the narrative for both films are incredibly similar, the main difference being that Blow-Up deals with images and The Conversation deals with audio.

I also did some background research into the mime, Robert Shields, and discovered that Union Square – the park in which the opening is set – is where Shields used to perform when he was younger, that he was very famous, had his own television show as part of an act called Shields and Yarnell and when he graduated highschool he joined a circus act. [5] [6]

[1]: The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film by Michael Ondaatje, published in 2002 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc (page 265)

[2]: The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film by Michael Ondaatje, published in 2002 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc (page 152)

[3]: Francis Ford Coppola by Robert K. Johnson, published in 1977 by Twayne Publishers (page 130)

[4]: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/watergate/part1.html

[5]: http://www.steveakash.com/robertshields/robert.html

[6]: http://www.robertshields.com/robert.html

Binary Oppositions

This wasn’t so much of a group exercise, but I feel it is relevant to post my findings for Binary Oppositions within the clip.

Binary Oppositions reduce complexity of the world within our culture and impose an order of things, though they are not necessarily always opposites. They seem to form a structure for the universe, pre-established rules that we must all abide by. Pre-established or God-given rules are a myth, however it is surprising how many people do not realise that things are a certain way because somebody made it that way to a certain end.

For example, advertisments for cleaning products are always aimed at women and by doing so are perpetuating the myth that women are all the cleaners within their households and actually enjoy doing it. The same goes for cars and the idea that when you by a car you are free.

The binary oppositions within The Conversation clip are as follows:

Sound / Silence

Public / Privacy

Trust / Paranoia

Truth / Lie

Distance / Closeness

Above / Below

Intertextuality, Hybridity & Genre

We did this research as a group exercise to begin with. We didn’t get very far as it was quite difficult to read intertextuality into our clip without much research.

There are several different types of intertextuality:

Intertextuality is the presence of signs within a piece of work, where these signs will be quoted from other works in order to give context to the current text.

Paratextuality refers to written texts, such as titles, captions, footnotes, etc.

Architextuality refers to genre identification.

Metatextuality is the critical commentry of other texts.

Hypotextuality is another text or genre that is transformed by this text.

Hypertextuality refers to direct connections to other texts.

In terms of The Conversation, intertextuality can be a difficult thing to observe from the opening scene. However it is there, most prevelantlty in the mime artist, in which his presence refers to the beginning and end of Blow-Up. The opening scene, a single shot slowly zooming in and following two characters – the mime, then Harry Caul – is possibly a reference to the opening of Orson Welles’ 1958 film Touch of Evil.

Harry Caul references Harry Haller from Hermann Hesse’s book Steppenwolf, but this is not made apparent in the opening scene – however Steppenwolf is in this scene. Jazz is an important part of the book, and the music we hear throughout the openening scene is just the kind of music from it. And we later learn that Caul plays the saxophone, just like one of the characters in Steppenwolf.

Touch of Evil video clip – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yg8MqjoFvy4 – accessed on 27/11/2010

Steppenwolf, written by Hermann Hesse, published by G. Fischer Verlag in 1927 (Germany)

Hal Lipset

As mentioned in a previous post, an article written about Hal Lipset was brought to Coppola’s attention which in turn, along with Blow-Up gave him inspiration for The Conversation.

Who is Hal Lipset? What was it about him that gave Coppola the idea for his film?

Hal Lipset was the most respected private detective in America during the 19040’s and was a chief investigator to Sam Dash on the Senate Watergate Committee in the 70’s. In 1947 he and his wife Lynn opened a detective agency in San Francisco with no money or contacts. In one early incident, a woman attempted to frame Lipset for rape but was foiled when his wife walked in holding a tape recorder.

As Hal chases jewel thieves across Europe, solves a family’s murder by accusing one of its own, and uncovers his own “Deep Throat” during Watergate (none other than reporter Bob Woodward), Holt draws more uncanny parallels between fact and fiction. Hal, she finds, is the kind of private eye we have seen before – a cynic who is really an idealist; a deductive reasoner; a former copy who is wary of the system; a longer who works outside the law.

Yet he’s also a rare breed of detective – a family man who hates guns; a salesman from the old school; a protester who testifies in Washington; an emotional, vulnerable, tough, angry entrepreneur who says he’s “in it for the money” but stands for just the opposite, the concept of free will in an increasingly conforming society.

– The Bug in the Martini Olive and Other True Cases from the Files of Hal Lipset, written by Patricia Holt, published in 1991 by Little Brown & Co.

It is interesting to see how alike Hal Lipset and the character of Harry Caul really are, not in personality but in their history and methods. In The Conversation Harry and his technician Stan work in what seems to be a warehouse, somewhere isolated where nobody would think of going so they could process recordings and develop new technologies for eavesdropping. So, it seemed, that Lipset and his own technician Ralph Bertsche did the same thing years before.

“To advance the art,” Time [magazine] wrote, “Hal Lipset, a seasoned San Francisco private eye, maintains a laboratory behind a false warehouse from where his eavesdropping ‘genius,’ Ralph Bertsche, works out new gimmicks such as a high-powered bug that fits into a pack of filter-tip cigarettes. It is padded to feel soft and shows the ends of real cigarettes to reassure a suspicious businessman or divorce-prone spouse…”

– The Bug in the Martini Olive and Other True Cases from the Files of Hal Lipset, written by Patricia Holt, published in 1991 by Little Brown & Co.

Lipset also served as a technical consultant on The Conversation, and did so with the proviso that they used only the most state-of-the-art technology available and be as realistic as possible “…with only one fib,” he says, “the pocket tape recorder does not have a playback function – and one exaggeration – the parabolic mic is too large to use secretly. I tried it once, looked through the telescopic lens, and saw my subject thumbing his nose at me.” [1] So is it possible, then, that without his advice on what equipment to use Coppola might not have known about the parabolic mic and consequentially wouldn’t have made the opening shot the way he did? It is very likely that Coppola would have found out about the mic and other technologies even without Lipset on hand, but it is interesting to note the extent of Lipset’s involvement and influence on the film.

[1]: http://www.spybusters.com/History_1965_Hal_Lipset.html – [accessed on the 17th/11/2010]

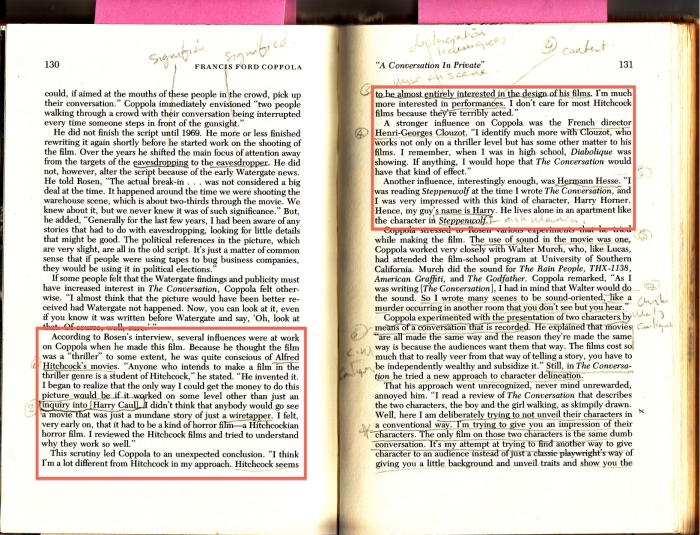

Influences

Coppola, it seems, was influenced by many works and people that he’d been a fan of. Hitchcock, as with many filmmakers, was one of them – but only in how he constructed his films. Coppola was more interested in the acting than the actual design, but he recognised that he would have to study Hitchcock if he was to design a thriller in the way he wanted. He states that he doesn’t care for most Hitchcock films because of the poor performances.

Steppenwolf, a book written by Hermann Hesse, was inspiration for Harry Caul. In the book the main character, also named Harry, is a reclusive and very private individual.

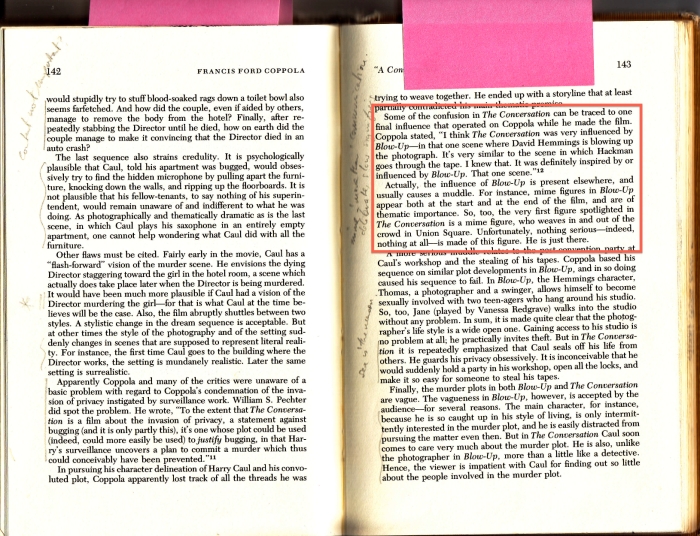

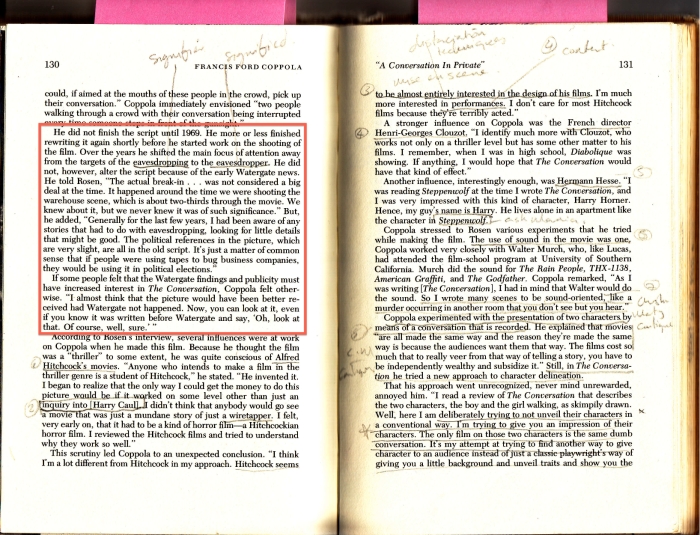

Pages taken from Francis Ford Coppola by Robert K. Johnson, published in 1977 by Twayne Publishers

Another large influence on Coppola was the film Blow-Up, directed by Michelangelo Antonioni. Blow-Up is about a photographer who, while taking pictures of a couple in a park, unknowingly captures a murder on film – a murder he thinks he has foiled until he blows up one of the pictures and sees the shadow of a man with a gun near the couple. He is pursued by a woman who wishes to retrieve the film from him and, eventually, has the film and photographs stolen from him – the corpse, which was left in the park, also disappears. [1] The story in this film is almost exactly the same as The Conversation, though with the obvious difference that Blow-Up uses film and The Converstion uses sound. Together these films seem to comment on the malleability of the media they focus on, that what you capture on film or audio tape can almost never be taken at face value, that there can always be something deeper and unnoticed – even innocuous in some cases.

[1]: http://www.filmsite.org/blow.html – Filmsite.org is written by Tim Dirks, Film Historian – http://www.linkedin.com/in/tdirks – both accessed on 15th/11/2010

There is also evidence elsewhere in The Conversation of Blow-Up‘s influence – the mime. In Antonioni’s film mime figures appear at the start and at the end of the film, as does the mime appear at the beginning of The Conversation.

Pages taken from Francis Ford Coppola by Robert K. Johnson, published in 1977 by Twayne Publishers

As the page below states, the script for The Conversation was written in the late sixties when Irvin Kershner brought to Coppola an article from Life magazine about a surveillance technician called Hal Lipset – like Harry Caul, Lipset worked out of San Francisco. Seeing this article, and having seen Blow-Up previously, gave Coppola the idea for The Conversation.

Pages taken from The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film by Michael Ondaatje, published in 2002 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc (page 152)

Watergate

From reading interviews and listening to the DVD commentary for The Conversation, one thing comes up fairly often: Watergate.

Watergate was a political scandal in the U.S in 1972 that culminated in Nixon’s resignation from office two years later. Burglars, attempting to plant or retrieve bugging devices, broke into the Watergate complex, which housed the Democratic party’s offices, were connected to President Nixon. An attempt to cover up this connection had been made by the President, and conversations between himself and others about the cover-up had also been recorded. On the surface this would seem like the perfect inspiration for The Conversation but in fact the film was over halfway through production at the time of the break-in and, while it would seem like they parallel each other almost perfectly, they have nothing to do with each other at all.

The script for The Conversation was finished before the seventies even began, though it is easy to see why people think the film was inspired by the Watergate scandal – having been released two years after the initial break-in and dealing with subject matter incredibly close to the scandal.

Pages taken from Francis Ford Coppola by Robert K. Johnson, published in 1977 by Twayne Publishers

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/watergate/part1.html – Accessed on 07/11/10